Gold Rush Lesson: Pacing a Lesson to Engage M4 Students

July 17, 2020

An important factor for supporting students’ learning is pacing each lesson in a flowing way to elicit motivation and maintain the interests for the learners according to their age. As teachers get to know students and can find the right combination and variety of tasks well-suited to students’ interests and skills, they are able to involve and engage students in the learning process. This is part of the craft of facilitating deeper learning.

An important factor for supporting students’ learning is pacing each lesson in a flowing way to elicit motivation and maintain the interests for the learners according to their age. As teachers get to know students and can find the right combination and variety of tasks well-suited to students’ interests and skills, they are able to involve and engage students in the learning process. This is part of the craft of facilitating deeper learning.

One reason why Teacher Praew enjoys teaching at Roong Aroon, she explains, is “I can be adaptable with the students, see what they want to learn each term, see their interests, and how I can adapt my activity to suit their interests. What I like about here is I can also try new approaches.” This term, she is experimenting with ways to give students more choices and to feel more involved in English classes, so that English is used increasingly for real reasons of communication.

In this term’s English M4 class, the theme is cause/effect: considering how one event can trigger others, and how every choice has consequences. For this week’s lessons, inspired by an old rhythmic song, Praew began learning more about the California Gold Rush, 1848-1852. Soon, she realized that it would be a fun topic for the Grade 10 (M4) students to explore. Indeed, most of them did not know anything about this pivotal part of American history. How would the story unfold with Thai students 172 years after the events occurred and an ocean away from here?

One might think teenagers would be bored by history, but it depends on how they are made to feel involved. Even history that is not their own can be made engaging when a teacher designs the lesson with their students in mind. By using an unknown part of history as the fulcrum for this lesson, English becomes the medium for communicating and its hurdles are forgotten once the desire to communicate is incited.

As she sets the computer up for the day, Teacher Praew asks students to get a coin from their lockers to set on their desk. They won’t be using it right away: “Just set it on your desk.” A small mystery is established about what it will be used for later.

After some conversation starters that engage students in friendly peer-to-peer interactions in English, Praew leads a grammar lesson that engages students with creative thinking too. There’s a rhythm to a simple Q/A process, and each question differs from the previous one so that curiosity is evoked and interest is maintained. Each question has been customized to her expanding knowledge and understanding of who her students are.

From the grammar, a smooth transition is made into the day’s main focus with two explicit questions about finding gold. One question evokes thinking about hypothetical facts: What would you do if you found gold? The second question elicits discussion about the consequences of finding gold, both positive and negative.

There are no right or wrong answers, and she keeps the discussion short, as the teacher observes the students’ levels of engagement with the questions. Then, she dramatically announces, “So this is the beginning of a whole story that changed the USA forever!”

Inputs about the Gold Rush history events are revealed step by step by several means: a song, a reading, a short video, a funny cartoon, an evocative “Gold Rush diary writing” activity. Each activity adds greater knowledge about how events are connected and give emotional depth to the history, inviting students to use their English skills simultaneously. Can this history of hardships be made engaging for 15-year old students?

The mystery of the unused coin is still on the desk waiting. It will have to keep waiting.

The mystery of the unused coin is still on the desk waiting. It will have to keep waiting.

After new vocabulary words are systematically introduced, a lonesome lyrical song captivates, even as students struggle to hear the words. There’s so much depth and emotion in the artist Dan Fogelberg’s voice that it draws most students into wanting to know the song’s meaning.

They listen again, more quietly attentive to the words, the second time reading along with the lyrics. Ah ha! Now they get more of it.

“So, what did students really learn from that?” Teacher Praew ponders. They learned about John Sutter’s mill, and how news of newly gold discovered in its creek spread “like wildfire” in 1848. They heard about how Sutter wished that he’d never found the gold, as people went crazy hoping to “strike it rich.” Was everything in the song true? No, in fact, it wasn’t John Sutter but James Marshall who found the first gold at Sutter’s Mill, Praew explains.

Later, one student reflected on his learning by integrating new words into his conversation; the slang phrase, “strike it rich” was appealing to a handful of students, something that they had never heard but it was easy for them to grasp its meaning.

Knowing how to pace the flow of a class emerges from each teacher’s experience, observing when the students are ready for the next activity, and the “mood shifts” in the larger class. After a funny cartoon video about “the 49ers,” students seem ready for a short history article, curious now to learn more. Given the option of two versions of the article, they may select either an easier or a harder article (with the same content). The teacher knows which version to encourage with which students, but it’s their choice. The reading expands their knowledge (and their English too) about a sudden migration to California when folks traveled westward like “herds of locusts.” The higher-level students work on their own with reading strategies well developed, while the teacher gives extra help to students whose reading skills need a bit of extra scaffolding.

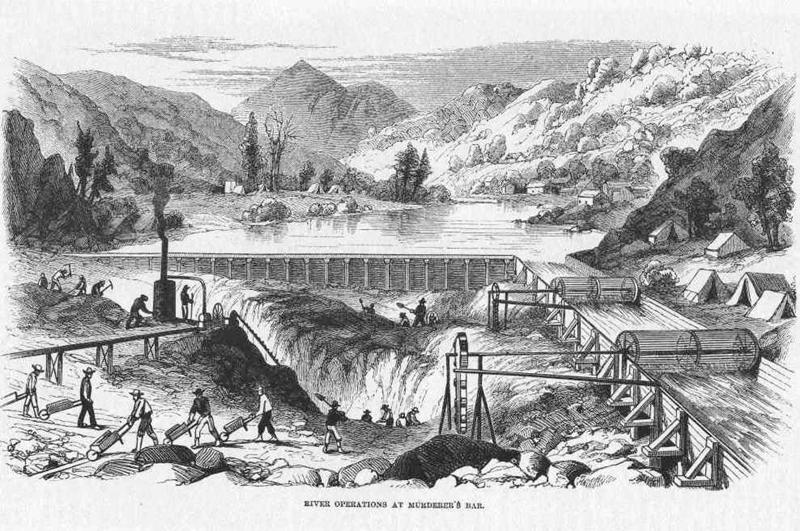

But what is that coin on the students’ desk for? What really were the factors that drove the decisions of the 1848-1852 pioneers to take such big risks to move so suddenly? How far is it from Boston to San Francisco? It’s 4,980 kilometers, teacher Praew explains, like traveling 2.5 times the length of Thailand from north to south, showing the distance to add impact with visual maps on a Google slide. And how big were the risks involved?

As students return from break, the teacher is jazzed and the students feel it as she asks in a lively voice, “Alright what are we going to do next? We’re going to journey from East to West.” She guides students into a custom-made coin-flipping / diary writing process in which they are invited to become American pioneers. Pioneers could afford little other than the covered wagons, horses, and food for the journey. They left the East with hopes for a better life in the unknown West when California had not even yet become a state.

Lessons at Roong Aroon are designed to engage students with questioning their own values by considering real events in deeper ways. This is done not by telling students what or how to think, but by giving opportunities for exploring and discovering diverse perspectives about events or issues.

The simulated journey allows students to discover how precarious the route westward was for pioneers. Each student experiences something different as they record a fictional but realistic personal diary. Flip 1 of the coin: heads — broken wagon wheel delays your trip; tales — you’re robbed and must replace all your supplies. Either way, “you decide to join up with other families for safety…” The journey continues. Flip 2: Heads — you’re feeling safer now, and start sharing homemade cookies with other travelers; tales — You’re feeling untrusting one night and sneak out of camp to get ahead of other travelers, but along the way… The journey continues, onward through the Rocky Mountains with unexpected travesties at every turn: a sick child, a rock slide, unfriendly townspeople, and much more.

As students tune into what heads/tales mean for their journey, they are developing the skills of listening for main ideas and summarizing. Teacher Praew slowly reads each outcome twice, so they get the gist and can then put it into their words, and write it on a structured diary sheet. They go slowly through this virtual journey, taking it one step at a time.

As students tune into what heads/tales mean for their journey, they are developing the skills of listening for main ideas and summarizing. Teacher Praew slowly reads each outcome twice, so they get the gist and can then put it into their words, and write it on a structured diary sheet. They go slowly through this virtual journey, taking it one step at a time.

Did Praew find this lesson activity online? No, she developed it herself, keeping in mind students’ personalities and their levels of English. It’s essentially a dictation activity, a task often disliked by ESL students as too difficult. By transforming dictation into a simulation game, not a single student complains, and all are curious to get to Flip 5 of their coin, to find out how their journey ends. One student explained that she liked playing the game because she had never played a game like that and felt as if she had a role in it, adding that she enjoys survival games too.

Teacher Praew reflected later on students’ engagement with the Gold Rush lesson:

I think they feel engaged because they don’t know what’s happening next, and I think they want to know. Yeah, I said: it’s their diary, their personal diary, and they want to know what’s going on with them in the next flip… They get to flip their own coin, and have their own destiny, have their own fortunes.

Later when reviewing students’ diary sheets, it was found that most students had written what the teacher had said, but some added feelings and a few created more story details from what they had been given (like how a fictional child had become sick).

Research/Theory Links: In educational theory and research, Praew’s approach would be described as a “communicative approach” to language learning, well supported by research. This story/lesson connects also with the learning technique of simulations, though the teacher discovered the technique by seeing the usefulness of it for herself and realizing how well it fit with that term’s Grade 10 English theme of choices and consequences.

Research/Theory Links: In educational theory and research, Praew’s approach would be described as a “communicative approach” to language learning, well supported by research. This story/lesson connects also with the learning technique of simulations, though the teacher discovered the technique by seeing the usefulness of it for herself and realizing how well it fit with that term’s Grade 10 English theme of choices and consequences.

At Roong Aroon School, teachers are challenged to develop new and creative lessons for their students. The same old activities often don’t work twice because the students have advanced and are ready for something different, so teachers must move along with the students. This unique, holistic approach gives teachers much freedom, but it also requires that lessons be designed and paced well, then adapted to the students in each class. When the core lesson is designed with an engaging rhythm and flow, adaptations often unfold more easily in relation to students as they are engaged with the learning process.