Supporting Learner Autonomy in Speaking More: English Conversation with Peers

July-August 2020

What is the value of getting students to talk amongst themselves? What would it look like? How does experimenting with your own “conversational approaches” help students engage in new ways of pushing their own boundaries and comfort zones? Why is this better than telling students what they should do?

What is the value of getting students to talk amongst themselves? What would it look like? How does experimenting with your own “conversational approaches” help students engage in new ways of pushing their own boundaries and comfort zones? Why is this better than telling students what they should do?

One strategy that has been experimented with at Roong Aroon is a series of activities at the beginning of every class: 5-minutes of “English only” in conversation with a friend. It was kept that simple, with only a little guidance on a weekly theme and some possible questions that might be asked.

Five Minutes of English Conversation with Friends

After nine years of English classes, 3-5 hours per week, Grade 10 students see how English can be used with foreigners and English teachers, but they are not yet confident in using English as a tool for communicating amongst themselves. Thai is their default language, in which they can easily communicate with greater nuance and speed. It’s ingrained in their neural networks, with words and phrases easily at their disposal after 15 years of hearing and using it every day, all day long.

So it was that Teacher Praew decided to set up 5-minutes at the beginning of every period for the whole term to be devoted to English speaking with friends.

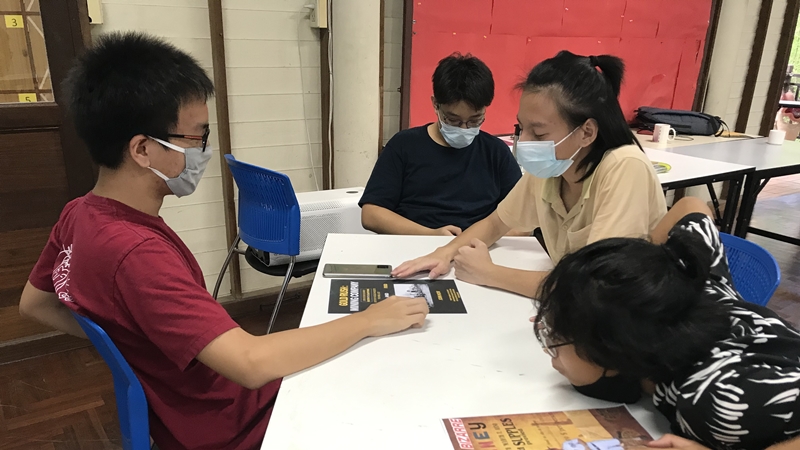

Each Grade 10 (M4) class begins with five minutes of pair work, doing simple conversation to inquire briefly into others’ perspectives on a broad theme, such as advertising. “What’s the funniest TV commercial you’ve ever seen?” or “Why is it necessary to advertise?”

The teacher encourages students to say whatever they want. Though, she understood it as not “full freedom” but a sort of “guided freedom” — as it started with a certain theme and suggested questions, but then they could answer however they wanted. She had emphasized: “No worries on grammar, just use their current vocabulary and say it naturally.”

The teacher encourages students to say whatever they want. Though, she understood it as not “full freedom” but a sort of “guided freedom” — as it started with a certain theme and suggested questions, but then they could answer however they wanted. She had emphasized: “No worries on grammar, just use their current vocabulary and say it naturally.”

The topics vary around common themes for conversation, aspects of daily life: food, movies, songs/artists, sports, and so forth. On the big screen at the front, about 12-16 questions are projected. Students may choose from questions on the board, or devise their own. Their choice. Each question is the kind that could lead into a good conversation, learning about each other. Some students use the questions on the board extensively, others go mostly in their own directions.

A timer is set, but Teacher Praew observes if all the pairs or triplets are actively engaged in English and may add a couple more minutes. Students hardly even realize when they go over on time. They are too busy discovering for themselves that YES, they CAN talk amongst themselves in English and maintain a full conversation, an eye opener to seeing the expanse of their own skills.

Following Day 1, students realize that after the conversation, they will be asked in informal, low-pressure ways to report about one thing that they learned about the other person. Thus, not only speaking but listening attentively becomes important too, like in any good conversation. Still, it’s a very non-judgemental activity, in which students naturally begin to help each other in expressing themselves more clearly.

Sometimes, the teacher enters as a third person for groups, as she walks around and notices when an extra boost is needed. She feels her role is to be “like the oil in an engine” to get them to go further, while the students’ own ideas provide the gears for making their conversational engine move forward. There is an implicit need to be a good listener, just as in reality when one engages with a good conversation.

Sometimes, the teacher enters as a third person for groups, as she walks around and notices when an extra boost is needed. She feels her role is to be “like the oil in an engine” to get them to go further, while the students’ own ideas provide the gears for making their conversational engine move forward. There is an implicit need to be a good listener, just as in reality when one engages with a good conversation.

After the initial 5-minutes is over, another 10 minutes is given to listening within the larger group as the teacher calls on each student, listening actively, paraphrasing their main ideas so everyone feels heard. She notices that for some students (but not all), the activity encourages empathy, as stronger students help weaker ones to simplify ideas so that they can better understand each other. The empathy was not forced; it happened autonomously as they chose to help a friend when they saw that help was needed.

How were Autonomy and Fun integrated in this one simple activity?

By the end of the term, Teacher Praew felt students were building a more confident inner voice about using English with friends: “I can do this activity and I can do it well.” In prior years many may only have spoken in formal, prepared presentations or super short conversations. Never before for 5 full minutes, informally and unplanned, with a friend.

At the end of the term, when the teacher surveyed students (anonymously) with a handful of open-ended questions, she asked “What activity did you like the most this term?” as well as “What activity would you like to continue next term?” Across her six Grade 10 classes, there was consistent positive feedback above 60% to both questions about “5 minutes English”; they wanted to continue it next term, far more than any other activity.

Why? Students explained: (1) “I like 5 minute English because it feels like I get to use real English, not just study about grammar” (2) “because we can share our opinion.” and (3) “I like 5 minutes talk because I can talk with friends because I think it make me improve my English more.”

From her informal observations and the review of the class evaluation survey, Teacher Praew explained that “5 minutes English” was something in which students felt they learned the most “because I feel that they enjoyed doing this the most. And when you enjoy doing something, that’s when you learn.”

In line with the Roong Aroon core value, they were also learning to maintain a “happy mindset” in relation to something that previously felt a little scary or intimidating to many, or at least made them nervous.

An unspoken agreement developed that friends were helping each other. Thus, some “freedom from fear” emerged as well. The fear of speaking English often comes from a fear of embarrassing oneself in front of friends. But this simple activity was set up so that friends could help one another, without any feeling of competition nor of saying “the wrong thing.” There were no right or wrong answers, a shared understanding that was reinforced by how T. Praew showed value in each answer through the quality with which she responded to and repeated every student’s answer during the whole class summary after the main 5 minute conversation.

Yes, the activity was evaluated, but not in an overt way to keep critical judgement far in the background. So, as the teacher observed students, she gave them 4% (of their final grade) at the end of each month. Most students earned full points for listening and conversing together over a sustained time. More importantly, they became confident in using English for a real conversation.